Adrian Kavanagh, 26th January 2018

As the Electoral (Amendment) (Dáil Constituencies) Bill 2017 was officially passed into law just before Christmas 2017, this will be the first polls analyses to use the new Constituency Commission electoral boundaries as the basis for the analysis. The translation of 2016 support figures onto these new constituency units is not a perfect one, alas, given the lack of tally figures in some cases (e.g. the Laois, Offaly and Kildare constituencies) or the lack of time to carry out the necessary background analyses in other cases (e.g. the constituencies in the West and North West). Where it has been possible to take account of tally figures, the constituency support estimates are based on the votes cast in the new constituency units in those cases.

The first two opinion polls of 2018 – the Sunday Times-Behaviour and Attitudes poll (21st January) and the Irish Times-Ipsos MRBI poll (25th January) – offer relatively good news for Fine Gael, although the party’s support level has dipped slightly relative to the level of support registered by the party in the December 2017 polls. Furthermore, the combined vote Fine Gael/Fianna Fáil vote share in these two polls stands at just under 60%. This, admittedly, is lower than the combined vote levels commanded by these parties before the onset of the Economic Crisis in 2008, but these poll figures seem to mark another stage in the recovery of the “Civil War” parties, given that the two parties won less than half of the votes cast nationally at the 2016 General Election. Is “Civil War” politics back? Maybe, maybe not…although it must be noted that when the other “Civil War” party, Sinn Fein, is factored in here, the combined support levels for the “Civil War parties” comes in between 75% and 80% in these two polls – up by over 15% on the combined support levels won by these parties at the 2016 election. As the larger parties advance, the smaller parties and Independents all fall back, while the Labour Party support levels remain significantly lower (especially in the Irish Times-Ipsos MRBI poll) than the already very low levels of support won by that party at the 2016 contest.

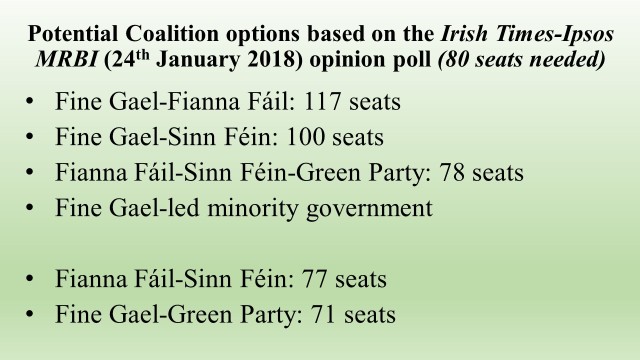

The 25th January 2018 Irish Times-Ipsos MRBI opinion poll estimates party support levels as follows: Fianna Fáil 25% (No Change relative to the previous Ipsos MRBI opinion poll), Fine Gael 34% (down 2%), Sinn Fein 19% (NC), Independents and Others 18% (up 2%) – including Solidarity-People Before Profit 2%, Social Democrats 1%, Green Party 3%, Independents 12% – Labour Party 4% (NC). My constituency-level analysis of these poll figures estimates that party seat levels, should such national support trends be replicated in an actual general election, would be as follows: Fianna Fail 47, Fine Gael 70, Sinn Fein 30, Green Party 1, Independents 12. (Fianna Fail 47, Fine Gael 69, Sinn Fein 29, Green Party 1, Independents 12 for the old 158-Dáil seats constituency arrangement.)

The 28th January 2018 Sunday Business Post-Red C opinion poll estimates party support levels as follows: Fianna Fáil 26% (No Change relative to the previous Red C opinion poll), Fine Gael 32% (up 5%), Sinn Fein 15% (down 1%), Independents and Others 21% (down 4%) – including Solidarity-People Before Profit 3%, Social Democrats 2%, Green Party 4%, Independents 12% – Labour Party 6% (NC). My constituency-level analysis of these poll figures estimates that party seat levels, should such national support trends be replicated in an actual general election, would be as follows: Fianna Fail 46, Fine Gael 70, Sinn Fein 22, Labour Party 4, Solidarity-People Before Profit 3, Green Party 2, Social Democrats 2, Independents 11. (Fianna Fail 45, Fine Gael 69, Sinn Fein 22, Labour Party 4, Solidarity-People Before Profit 3, Green Party 2, Social Democrats 2, Independents 11 for the old 158-Dáil seats constituency arrangement.)

The 21st January 2018 Sunday Times-Behaviour & Attitudes opinion poll estimates party support levels as follows: Fianna Fáil 26% (No Change relative to the previous Behaviour & Attitudes opinion poll), Fine Gael 32% (down 2%), Sinn Fein 18% (up 1%), Independents and Others 18% (NC) – including Solidarity-People Before Profit 2%, Social Democrats 1%, Green Party 2%, Independents 13% – Labour Party 6% (up 1%). My constituency-level analysis of these poll figures estimates that party seat levels, should such national support trends be replicated in an actual general election, would be as follows: Fianna Fail 49, Fine Gael 65, Sinn Fein 29, Labour Party 3, Independents 14. (Fianna Fail 47, Fine Gael 66, Sinn Fein 28, Labour Party 3, Independents 14 for the old 158-Dáil seats constituency arrangement.)

Independents and Others: Support levels for independents (whether as part of the Independent Alliance or other alliances such as the Independents4Change grouping, or for “non-aligned” independents) are down significantly on the support levels enjoyed by these groupings at February 2016 election. If these figures were to be replicated in a general election contest, a significant number of Independent Dail deputies would lose their seats, or would at least face a major struggle to hold these. Improved support levels for Fine Gael, Fianna Fail and Sinn Fein, relative to their February 2016 General Election performances, also place greater pressure on the independents and smaller parties in terms of translating votes into seat levels, as seats that may otherwise gone to Independents/smaller party candidates may now be won instead by a candidate from the larger parties, arising from their overall increase in support levels.

In the lead up to the February 2016 election, seat levels for the Independents and Others grouping were notably harder to glean than was the case for the larger political parties, given that this is a very large and diverse grouping. The general election showed that, in some cases, increased support levels for a smaller party were simply absorbed by the increased number of candidates within that party/grouping, meaning that increased support levels did not translate into increased seat numbers – as evidenced in the support/seat level figures for the Social Democrats in that election. These trends could also be evidenced when the 2002 and 2007 Sinn Fein vote and seats levels were compared. It was impossible to apply the model in the case of the smaller parties/groupings ahead of the 2016 General Election, as many of these smaller parties and groupings did not exist in 2011 or had contested only a relatively small number of constituencies. But, with a good number of these parties having contested a number of constituencies in the 2016 election, it is now possible to treat them as separate entities in this model (although figures can not be gleaned for constituencies that these parties did not contest on February 26th, as in the case of the Social Democrats in more than twenty of the current Dail constituencies).

The nature of the Independents and Others grouping means that support levels do not usually translate as neatly into seat gains as would be the case with parties such as Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. Vote transfer levels across this grouping will generally not prove to be as strong as the extent of intra-party vote transfer levels enjoyed by the larger political parties, who in turn often enjoy a “seat bonus” at most general election contests. Against that, candidates from the Independents and Others grouping may be more likely to attract transfers from political parties than would be the case with candidates from other political parties, as indeed proved the case in certain circumstances (most notably Maureen O’Sullivan in Dublin Central) at the 2016 election. And, of course, the better that candidates from this grouping fare in different constituencies, the more likely they are to attract vote transfers given that they will be placed higher up in the order of first preference vote levels and hence well placed to last longer/until the end of the election count.

Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael surge: When compared with the February 2016 election results and particularly the trend evidenced in polls carried out in the months leading up to that election, the opinion polls published across the first few weeks of 2017 amounted to another set of very good opinion polls for Fianna Fáil. (Although party support levels were not as high as they stood at in the Ipsos-MRBI opinion poll of 7th July 2016, which has represented the best poll figures for that party since the Spring of 2008; a point in time when Fianna Fáil were still the strongest party in the state by some considerable distance.) Fianna Fáil’s strength in the opinion polls in the earlier part of 2017 has been eclipsed somewhat by the rise of Fine Gael in the latter part of 2017, however, and this trend continues also into the first opinion polls of 2018.

An increase in Fianna Fáil support levels of around seven percentage points between the 2011 and 2016 elections translated into an even more increase in seat levels for that party, although the reasons for this have been discussed in earlier poll analyses (including the impact of the 2012 Constituency Commission report). (A similar trend was noted in 2011 in respect to the support/seat gains made by Fine Gael.) It has to be expected that an even larger increase in Fianna Fáil support levels than that evidenced at the February 2016 election, or an even larger increase in Fine Gael support levels, than those evidenced at the 2011 election, would translate into very significant seat gains for either of, or both of, those parties at a future general election, especially if they could avail of the seat bonus that the largest party, or parties, usually gets at Irish general elections; the proportional element of the Irish electoral system notwithstanding. The final seat estimates for Fine Gael and Fianna Fail here may well veer on the conservative side of the scale (although both of these parties are still seen to be enjoying a significant seat bonus in all of these poll analyses), mainly due to the need to assume that vote management patterns would remain roughly the same as at 2016 to ensure that there is a consistency in approach across the post-General Election poll analyses. (I have now relaxed the assumption that parties would run the same number of candidates as in February 2016, mainly due to the realisation that a party such as Fianna Fail is likely to be running extra candidates in a number of constituencies (e.g. Limerick, Limerick City, Cork North-Central, Meath East) arising from their observations of party support trends at that election.) With the vote management assumption being further relaxed somewhat, Fianna Fail are well placed to win a seat-level in the mid-to-high 50s range on the support patterns evident in this poll.

The impact of the new constituency boundaries may be evidenced in the figures listed above. In the Irish Times poll, which shows Fine Gael nine percentage points ahead of Fianna Fáil, it is Fine Gael who seems to be the party who is benefiting the most from the new constituency boundary arrangements (with potential gains in Cavan-Monaghan and Kildare South offsetting a potential loss in Dublin North-West). However, when the gap between the two larger parties narrows, as in the case of the Sunday Times-Behaviour & Attitudes poll (six percentage point gap), the new constituency arrangement does seem to weight heavily in favour of Fianna Fáil. In this scenario the party does forfeit the potential of a second seat in the old Offaly three-seater (although prospects of three seats in Laois-Offaly cannot be ruled out), but – on the basis of the figures in the Sunday Times-Behaviour & Attitudes analysis – the party would seem to be well placed to make further seat gains in Kildare South (almost mirroring Fine Gael’s success in Dún Laoghaire in 2016), Dublin Central and Dublin North-West. The addition of the West Cavan area (the impact of which has not been factored in here) is also likely to copperfasten the party’s hold on their second seat in that constituency; something that this analysis has not been able to take account of.

The problem for Labour: Like the canary in the coal mine, the constituency level poll analyses consistently warned in the years leading up to the 2016 General Election that low levels of Labour support nationally would translate into very low seat levels for that party. Given the Labour Party’s geography of support, but also given the increased level of opposition the party faces on the left of the political spectrum from Sinn Fein, Solidarity-People Before Profit, the Social Democrats and other left-wing groupings/independent candidates, it was argued that Labour would struggle to convert votes into seats if their national support levels fall below the 10% level, as indeed proved to be the case with the February 26th election. If the party’s support levels nationally were to even lower than the 6.6% level won in the general election, then the party would be losing even more seats – especially given the narrow margins that Labour candidates (such as Willie Penrose) won seats by in that election. On the 4% support level evident in the Irish Time-Ipsos MRBI poll, Labour would face a struggle to win seats in every constituency in the state, even in their strongest areas. On these national support figures and assuming they would be contesting at least thirty constituencies, the Labour Party would need a lot of luck to win more than one or two seats in terms of their total number of seats at a general election contest. There would be a relatively strong possibility that Labour could end up winning no seats.

The low support level in this poll is a problem, but some Labour marginals and some potential Labour seat gains would be also swallowed up by the stronger showings for other parties, such as Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin. On the figures in this analysis the party would really only be competitive in only a handful of constituencies and – if vote transfers patterns did not favour them – there could be a not-entirely impossible scenario emerging in which that party, based on these poll numbers (a 4% support level nationally), could end up winning no seats in a general election. On the other hand, the party seat estimates do improve on the basis of the 6% support level figure in the Sunday Times poll and Labour could edge out another seat or two in constituencies, such as Dublin Fingal, if problems were to exist with the vote management approaches of other political parties or groupings, as indeed happened in a number of constituencies at the February 2016 contest, or if the party vote was to hold up especially well in a small number of constituencies.

How this model works: Constituency support estimates for different parties and groupings form the basis of the general approach taken with this analysis. This seeks to ask the following question in relation to different opinion poll results – what do these poll figures mean in terms of the likely number of Dail seats that could be won by the different parties and groupings on those national support levels? Although the Irish electoral system is classified as a proportional electoral system, the proportion of seats won by parties will not measure up exactly to their actual share of the first preference votes, mainly because geography has a very significant impact here. First preference votes need to be filtered through the system of Irish electoral constituencies (and the different numbers of seats that are apportioned to these). In order to address this question, I estimate what the party first preference votes would be in the different constituencies, assuming similar (proportional) changes in party vote shares in all constituencies to those that are being suggested by a particular opinion poll. This of course is a very rough model and it cannot take appropriate account of the fact that changing support levels between elections tend to vary geographically, while it also fails to take account of the local particularities of the different regions in cases where no regional figures are produced in association with different national opinion polls meaning that there is no scope to carry out separate regional analyses based on these poll figures.

Thus constituency support estimates for different parties/groupings will be over-estimated in some constituencies and under-estimated in others, but the expectation would be that the overall national seat figures figures estimated will be relatively close to the true level, given that over-estimates in certain constituencies will be offset by under-estimates in others. Based on these estimated constituency support figures, I proceed to estimate the destination of seats in the different constituencies. The constituency level analysis involves the assigning seat levels to different parties and political groupings on the basis of constituency support estimates and simply using a d’Hondt method to determine which party wins the seats, while also taking account of the factors of vote transfers and vote splitting/management (based on vote transfer/management patterns observed in the February 2016 election). Due to unusually high/low support levels for some parties or political groupings in certain constituencies in the previous election, the model may throw up occasional constituency predictions that are unlikely to pan out in a “real election”, but of course the estimates here cannot be seen as highly accurate estimates of support levels at the constituency level as in a “real election” party support changes will vary significantly across constituency given uneven geographical shifts in support levels.

The model has been amended to take account of instances where general election candidates have changed their political party/political grouping, as with the case of Stephen Donnelly’s (Wicklow) defection from Social Democrats, return to the Independent ranks and his later joining of the Fianna Fail party. In this instance, part (i.e. 50%) of that candidate’s February 2016 support level is transferred from the old party’s tally to the new party/political grouping when carrying out analyses with this model, with the remainder being allocated to/remaining with that candidate’s old political party/political grouping.

The point to remember here is that the ultimate aim of this model is to get an overall, national-level, estimate of seat numbers and these are based, as noted earlier, on the proviso that an over-prediction in one constituency may be offset by an under-prediction in another constituency. This model does not aim, or expect, to produce 100% accurate party support and seat level predictions for each of the 39 constituencies. (Just taking a moment to mourn the loss of the three-seat Laois constituency…)

These analyses simply estimate what party seat levels would be, should such national support trends be replicated in an actual general election. For a variety of reasons (including the impact of high levels of undecided voters in a specific poll), the actual result of an election contest may vary from the figures suggested by an opinion poll, even if the poll is carried out relatively close to election day, or on election day itself as in the case of exit polls, but the likelihood of such variation is not something that can be factored into this model. Vote transfer patterns of course cannot be accounted for in the constituency support estimate figures, but I do try to control for these somewhat in my set of amended seat allocations.

Constituency Support Estimates (Irish Times-Ipsos MRBI poll): The constituency support estimates based on the Irish Times-Ipsos MRBI opinion poll (25th January 2018) are as follows:

| Constituency | FF | FG | LB | SF | IND | OTH |

| Carlow-Kilkenny | 40% | 34% | 4% | 16% | 2% | 6% |

| Cavan-Monaghan | 26% | 36% | 0% | 31% | 5% | 2% |

| Clare | 31% | 34% | 5% | 10% | 17% | 3% |

| Cork East | 26% | 40% | 8% | 15% | 7% | 5% |

| Cork North Central | 29% | 24% | 4% | 27% | 4% | 12% |

| Cork North West | 34% | 41% | 0% | 9% | 13% | 3% |

| Cork South Central | 39% | 32% | 2% | 16% | 5% | 5% |

| Cork South West | 20% | 42% | 4% | 11% | 21% | 2% |

| Donegal | 29% | 19% | 0% | 35% | 16% | 1% |

| Dublin Central | 13% | 24% | 6% | 30% | 16% | 11% |

| Dublin Mid West | 16% | 34% | 3% | 30% | 8% | 9% |

| Dublin Fingal | 26% | 29% | 6% | 13% | 19% | 7% |

| Dublin Bay North | 17% | 32% | 5% | 18% | 19% | 9% |

| Dublin North West | 14% | 15% | 4% | 46% | 5% | 16% |

| Dublin Rathdown | 11% | 42% | 6% | 10% | 21% | 11% |

| Dublin South Central | 14% | 20% | 5% | 34% | 15% | 12% |

| Dublin Bay South | 13% | 43% | 7% | 14% | 4% | 19% |

| Dublin South West | 16% | 32% | 4% | 22% | 14% | 13% |

| Dublin West | 18% | 31% | 10% | 21% | 7% | 13% |

| Dun Laoghaire | 19% | 49% | 5% | 7% | 4% | 15% |

| Galway East | 27% | 40% | 6% | 9% | 16% | 2% |

| Galway West | 26% | 33% | 3% | 13% | 19% | 6% |

| Kerry County | 17% | 30% | 4% | 17% | 30% | 2% |

| Kildare North | 32% | 35% | 6% | 10% | 3% | 14% |

| Kildare South | 35% | 38% | 7% | 15% | 4% | 2% |

| Laois-Offaly | 35% | 30% | 2% | 21% | 9% | 3% |

| Limerick City | 28% | 37% | 7% | 17% | 1% | 9% |

| Limerick | 27% | 47% | 0% | 10% | 13% | 3% |

| Longford-Westmeath | 29% | 32% | 5% | 13% | 18% | 3% |

| Louth | 18% | 25% | 5% | 38% | 7% | 7% |

| Mayo | 24% | 58% | 0% | 12% | 4% | 1% |

| Meath East | 25% | 43% | 3% | 18% | 8% | 3% |

| Meath West | 24% | 37% | 2% | 29% | 5% | 3% |

| Roscommon-Galway | 22% | 23% | 2% | 11% | 41% | 2% |

| Sligo-Leitrim | 30% | 34% | 2% | 23% | 9% | 2% |

| Tipperary | 26% | 23% | 7% | 11% | 30% | 2% |

| Waterford | 20% | 36% | 3% | 24% | 12% | 6% |

| Wexford | 28% | 32% | 9% | 14% | 13% | 4% |

| Wicklow | 24% | 41% | 2% | 22% | 4% | 7% |

Please Note: “OTH” here refers to the total support/seat levels estimated for the smaller parties (including the Greens, Social Democrats, Solidarity-People Before Profit and Renua – as the published version of an earlier post showed, it gets “messy” if there are too many columns in the tables here!

Seat Estimates: Based on these constituency estimates and using a d’Hondt method to determine which party wins the seats in a constituency, the party seat levels are estimated as follows:

| Constituency | FF | FG | LB | SF | IND | OTH |

| Carlow-Kilkenny | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cavan-Monaghan | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Clare | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cork East | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cork North Central | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cork North West | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cork South Central | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cork South West | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Donegal | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Dublin Central | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Dublin Mid West | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Dublin Fingal | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Dublin Bay North | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Dublin North West | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Dublin Rathdown | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Dublin South Central | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Dublin Bay South | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Dublin South West | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Dublin West | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Dun Laoghaire | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Galway East | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Galway West | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Kerry County | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Kildare North | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kildare South | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Laois-Offaly | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Limerick City | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Limerick | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Longford-Westmeath | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Louth | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Mayo | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Meath East | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Meath West | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Roscommon-Galway | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Sligo-Leitrim | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Tipperary | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Waterford | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Wexford | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Wicklow | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| STATE | 43 | 71 | 0 | 30 | 15 | 1 |

Amended Seat Estimates: The seat estimates also need to take account of the candidate and competition trends unique to the different constituency. Amending the model to account for seats that may be won or lost on the basis of estimates here being based on support levels derived due to a large/small number of candidates contesting the election. The vote transfer/management patterns evidenced in the February 26th contest are also being factored in to a certain degree. The assumption that political party vote management patterns will remain consistent/similar to those of February 26th does result in some conservative seat estimates in the case of parties that experience notable increase in support levels, , but it is important to maintain a consistency in approach across all of these post-General Election 2016 poll analyses. I have now relaxed the assumption that candidate selection approaches (i.e. the number of candidates selected) would remain the same for the February 26th contest. It would be more than fair to assume, for instance, that Fianna Fail will run more than one candidate in constituencies such as Laois, Limerick City, Cork North-Central and Meath East and Sinn Fein will run more than one candidate in Dublin Mid-West, on the basis of the support trends/patterns that were evident in such constituencies at the February 2016 election, but also on the basis of the party’s stronger support levels in recent opinion polls. However, the model, of course, cannot take account of constituencies that were not contested by certain political parties/groupings.) Taking these concerns into account, the amended seat allocations across the constituencies would look more like this:

| Constituency | FF | FG | LB | SF | IND |

| Carlow-Kilkenny | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cavan-Monaghan | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Clare | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cork East | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cork North Central | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cork North West | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cork South Central | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cork South West | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Donegal | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Dublin Central | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Dublin Mid West | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Dublin Fingal | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Dublin Bay North | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Dublin North West | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Dublin Rathdown | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Dublin South Central | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Dublin Bay South | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dublin South West | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Dublin West | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Dun Laoghaire | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Galway East | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Galway West | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Kerry County | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Kildare North | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kildare South | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Laois-Offaly | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Limerick City | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Limerick | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Longford-Westmeath | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Louth | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Mayo | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Meath East | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Meath West | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Roscommon-Galway | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sligo-Leitrim | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Tipperary | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Waterford | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Wexford | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Wicklow | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| STATE | 47 | 70 | 0 | 30 | 12 |

| % Seats | 29.7 | 44.3 | 0.0 | 19.0 | 7.6 |

Fine Gael (and also Fianna Fáil) are obviously gaining from a larger party seat bonus in this most recent series of polls analysis, as illustrated in the Ipsos-MRBI poll analysis figures above. As noted earlier, some of the seats estimates here may veer on the conservative side. If either of the two larger parties were to manage the party vote more effectively in some constituencies than they did in February 2016, then the likelihood is that the support patterns evident in this opinion poll would translate into a higher number of seats for either of these parties. It is worth noting also that these figures show the three larger parties accounting for over eighty percent of the seats being allocated by this model. This almost parallels the dominance of the Irish political landscape (in terms of seat levels, especially) by the old two-and-a-half party system of Fianna Fail, Fine Gael and Labour. Given that current Sinn Fein support levels are notably closer to those of Fine Gael and Fianna Fail that was the case with Labour for most of the State’s history, if these support trends were to pan out in future elections it could well be the case that a new “three party system” could well be replacing the old “two-and-a-half party system”. This is not, of course, to downplay the significant level of support that is still commanded by the Independents and Others grouping, even given the declining support levels for independents across most recent polls, but this grouping – as discussed in detail above – does face greater challenges in terms of translating support levels into seat gains than would be the case for the larger political parties.

Potential Governments?: As the image above shows, on the basis of the seat-estimate numbers in this poll analysis, two-party coalitions involving Fine Gael and either Sinn Féin or Fianna Fáil would both be viable options. On the basis of the precedent set after the February 2016 General Election, it would also be possible to conceived of a minority government, led either by Fine Gael (and maybe also Fianna Fáil, although this would seem a less likely prospect based on these numbers), involving a number of deputies from the independents and smaller parties groupings, but such an arrangement would need the support from one (or both) of the other two larger parties in order for this to be viable.

Why are Labour likely to win less seats than they did in 1987 on a similarly low national support level?: The seat level estimates for the Labour Party in most of the poll analyses more or less from 2013 onwards have been stark; also highlighting the fact that the PR-STV system is proportional, but only to a limited extent. Previous analyses have, moreover, suggested that, especially given the increased competition on the Left from Sinn Fein, other smaller left of centre parties and left-leaning independents, that it will be a struggle for Labour to win seats in most, if not all, constituencies if the party’s national support levels fall below the ten percent level, as has been shown in similar analyses of most recent polls. The further the party falls below this ten percent level, the more problems Labour faces in terms of winning seats. Labour would be in serious trouble if their national support levels fall below ten percent as the party is also facing a “perfect storm” from electoral geography and changed competition levels. These factors include the reduction in Dail seat numbers (from 166 to 158) and other changes made to general election boundaries by the 2012 Constituency Commission (which militated against Labour while seeming to advantage other parties, but notably Fianna Fail) as well as the increased competition the party now faces on the Left from Sinn Fein, other smaller left-wing parties and left-of-centre independents, as well as from Fianna Fail. When Labour support levels fell to similarly low levels in the late 1990s and early-to-mid 2000s, the party was in a position to be helped (as in the 1997, 2002 and 2007 General Elections) by transfers from lower placed candidates from the smaller left-wing parties. But on these constituency-estimate figures outlined in these analyses Labour Party candidates would find themselves polling below candidates from Sinn Fein, the Socialist Party, the Workers and Unemployed Action Group or the People Before Profit Alliance, or left-leaning independents, in a number of constituencies. Instead of being in a position to possibly benefit from vote transfers (which themselves would be likely to dry up in any case), the Labour candidates would now in a number of cases be eliminated before the final count and would be providing the transfers to see candidates from other left-of-centre political groupings over the line. (If we look at the 1987 case study – we see Labour won 6.5% of the vote in the 1987 General Election and won 12 seats, but it is also worth noting that they did not contest nine constituencies in that election, whereas their 7% national vote is being distributed across all forty constituencies in this analysis, as with the most recent general elections in which Labour has contested all constituencies. In two of the twelve constituencies in 1987 where Labour won seats – Dublin South-Central, Dublin South-West, Galway West and Wexford – vote transfers were crucial in ensuring Labour won these these seats – i.e. Labour candidates were outside the seat positions on the first count but overtook candidates with higher first preference votes as counts progressed due to transfers from other candidates.

| Constituency | FPV | Total Poll | Quota | % FPV | Lab/quota |

| Carlow-Kilkenny | 7,358 | 57,485 | 9,581 | 12.80 | 0.77 |

| Cork South-Central | 4,862 | 56,259 | 9,377 | 8.64 | 0.52 |

| Dublin South-Central | 4,701 | 51,692 | 8,616 | 9.09 | 0.55 |

| Dublin South-East | 3,480 | 38,270 | 7,655 | 9.09 | 0.45 |

| Dublin South-West | 5,065 | 41,454 | 8,291 | 12.22 | 0.61 |

| Dun Laoghaire | 6,484 | 55,702 | 9,284 | 11.64 | 0.70 |

| Galway West | 3,878 | 52,762 | 8,794 | 7.35 | 0.44 |

| Kerry North | 6,739 | 34,764 | 8,692 | 19.38 | 0.78 |

| Kildare | 7,567 | 53,705 | 8,951 | 14.09 | 0.85 |

| Louth | 6,205 | 46,809 | 9,362 | 13.26 | 0.66 |

| Wexford | 5,086 | 52,922 | 8,821 | 9.61 | 0.58 |

| Wicklow | 7,754 | 46,003 | 9,201 | 16.86 | 0.84 |

Voting statistics for constituencies in which Labour won seats at the 1987 General Election. The table above shows that there was no constituency in 1987 in which a Labour candidate exceeded the quota and indeed successful Labour candidates, Ruairi Quinn and Michael D. Higgins won seats in their constituencies despite winning less than half of the quota in their first preference votes. In addition, Dick Spring came within a handful of votes of losing his seat in Kerry North.)

The Labour Party has tended to fall below the ten percent level in most opinion polls over the past few years, as is especially evident in this Ispsos-MRBI opinion poll. Labour seat level estimates in most of the poll analyses I have carried out in the years leading up to the recent general election were quite stark, highlighting the fact that our PR-STV electoral system is proportional but only to a limited extent. The party’s seat levels in the actual election generally tended to support the analysis offered by this model. The further Labour Party support nationally falls below the ten percent level, the more difficulties it will face in terms of winning seats. This proved to be the case in February 2016 as Labour was left to face a “perfect storm” from the combined effects of boundary changes, electoral geography and changing political competition patterns. These factors explain why Labour faces greater challenges in translating lower levels of national support into seat numbers than it did back in 1987 when the party won 12 seats with just over six percent of the national vote.

- The size of the Dáil was reduced from 166 seats to 158 at the recent general election, but my analysis of the effects of these boundary changes suggested that Labour would be more adversely effected by these than other parties, such as Fianna Fáil in particular, would be. Had the new boundaries been in place in 2011, it was estimated that the Labour Party would probably have won three or four fewer seats, while Fianna Fáil may have won two or three more seats.

- While there is a distinct geography to Labour Party support levels over and above the more “catch-all” trends traditionally associated with Fianna Fáil and (to a lesser degree) Fine Gael, there is not the same concentration of support into a small number of constituencies that one has observed in past contests with smaller parties such as the Green Party (especially in the 2002 and 2007 contests, as well as the 2016 contest) and parties such as the Social Democrats and Anti Austerity Alliance-People Before Profit in the 2016 election. In the latter cases, lower support levels nationally often translate into much larger support levels in a small number of stronger constituencies, allowing these to pick up a number of Dáil seats. In the case of Labour, the same spiking of support in a small number of stronger constituencies is not evident. As evidenced at the 2016 contest, a small share of the vote nationally (especially if Labour contests all, or most of, the Dáil constituencies) would translate into a sufficient level of support to allow them to challenge for seats in only a very small number of their stronger constituencies. (Labour were also not be helped by the level of defections and retirements amongst its cohort of TDs, especially given that these involve many of the party’s stronger constituencies at the 2011 contest. This was perhaps most evident in the party’s failure to win seats in some of its strongest constituencies in 2011, namely Dublin South-West, Dublin South-Central and Dublin North-West.)

- In 1987, Labour won 12 seats even though the party never exceeded the quota in any of the constituencies being contested by the party in that election (and it is worth remembering that Labour did not contest every constituency in 1987). Indeed, Labour won nearly half of their seats in constituencies where they had won little more than half a quota in terms of first preference votes – or even less than half a quota in the case of the Galway West and Dublin South-East constituencies. Labour were helped in this instance as their candidates were in a position to pick up vote transfers from lower-placed left-wing candidates, as well as lower-placed Fine Gael candidates (arising from that party’s drop in support in 1987 and also some instances of poor vote management). In 2002 and 2007 Labour were also able to translate their national support levels into a higher proportion of Dáil seat levels due to Labour candidates being ahead of candidates from other left-wing groupings and hence in a position to win transfers from these. In the context of low Labour support levels nationally in the 2016 election, however, the trend in a number of constituencies was instead for Labour Party candidates to be polling below candidates from Sinn Fein, the Social Democrats, Solidarity-People Before Profit, or left-leaning independents. Instead of being in a position to possibly benefit from left-wing vote transfers (which themselves were weaker in any case, as was predicted earlier in data provided in a Sunday Independent-Millward Brown poll in the summer of 2015), in this context Labour candidates were eliminated before the final count in many constituencies and potentially providing the transfers to ensure the election of candidates from other left-of-centre political groupings (or Fine Gael candidates). In previous elections, Labour might still have been able to translate lower support levels into seats in constituencies such as Dublin Bay-South, Dublin Bay-North, Clare and Dublin Rathdown, but this proved not to be the case in the 2016 contest. Ironically, with the party now out of government, they may find that their ability to win vote transfers improves again over time, along the lines of the trends that were observed for the Green Party at the 2016 General Election.